byname HEROD

THE GREAT, Latin HERODES MAGNUS Roman-appointed king of Judaea (37-4 BC),

who built many fortresses, aqueducts, theatres, and other public buildings

and generally raised the prosperity of his land but who was the centre

of political and family intrigues in his later years. The New Testament

portrays him as a tyrant, into whose kingdom Jesus of Nazareth was born.

byname HEROD

THE GREAT, Latin HERODES MAGNUS Roman-appointed king of Judaea (37-4 BC),

who built many fortresses, aqueducts, theatres, and other public buildings

and generally raised the prosperity of his land but who was the centre

of political and family intrigues in his later years. The New Testament

portrays him as a tyrant, into whose kingdom Jesus of Nazareth was born.

When Pompey (106-48 BC) invaded Palestine in 63 BC, Antipater supported his campaign and began a long association with Rome, from which both he and Herod were to benefit. Six years later Herod met Mark Antony, whose lifelong friend he was to remain. Julius Caesar also favoured the family; he appointed Antipater procurator of Judaea in 47 BC and conferred on him Roman citizenship, an honour that descended to Herod and his children. Herod made his political debut in the same year, when his father appointed him governor of Galilee. Six years later Mark Antony made him tetrarch of Galilee. In 40 BC the Parthians invaded Palestine, civil war broke out, and Herod was forced to flee to Rome. The senate there nominated him king of Judaea and equipped him with an army to make good his claim. In the year 37 BC, at the age of 36, Herod became unchallenged ruler of Judaea, a position he was to maintain for 32 years. To further solidify his power, he divorced his first wife, Doris, sent her and his son away from court, and married Mariamne, a Hasmonean princess. Although the union was directed at ending his feud with the Hasmoneans, a priestly family of Jewish leaders, he was deeply in love with Mariamne.

During the conflict between the two triumvirs Octavian and Antony, the heirs to Caesar's power, Herod supported his friend Antony. He continued to do so even when Antony's mistress, Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt, used her influence with Antony to gain much of Herod's best land. After Antony's final defeat at Actium in 31 BC, he frankly confessed to the victorious Octavian which side he had taken. Octavian, who had met Herod in Rome, knew that he was the one man to rule Palestine as Rome wanted it ruled and confirmed him king. He also restored to Herod the land Cleopatra had taken. Herod became the close friend of Augustus' great minister Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, after whom one of his grandsons and one of his great-grandsons were named. Both the emperor and the minister paid him state visits, and Herod twice again visited Italy. Augustus gave him the oversight of the Cyprus copper mines, with a half share in the profits. He twice increased Herod's territory, in the years 22 and 20 BC, so that it came to include not only Palestine but parts of what are now the kingdom of Jordan to the east of the river and southern Lebanon and Syria. He had intended to bestow the Nabataean kingdom on Herod as well, but, by the time that throne fell vacant, Herod's mental and physical deterioration made it impossible.

Herod endowed his realm with massive fortresses and splendid cities, of which the two greatest were new, and largely pagan, foundations: the port of Caesarea Palaestinae on the coast between Joppa (Jaffa) and Haifa, which was afterward to become the capital of Roman Palestine; and Sebaste on the long-desolate site of ancient Samaria. In Jerusalem he built the fortress of Antonia, portions of which may still be seen beneath the convents on the Via Dolorosa, and a magnificent palace (of which part survives in the citadel). His most grandiose creation was the Temple, which he wholly rebuilt. The great outer court, 35 acres (14 hectares) in extent, is still visible as Al-Haram ash-Sharif. He also embellished foreign cities--Beirut, Damascus, Antioch, Rhodes--and many towns. Herod patronized the Olympic Games, whose president he became. In his own kingdom he could not give full rein to his love of magnificence, for fear of offending the Pharisees, the leading faction of Judaism, with whom he was always in conflict because they regarded him as a foreigner. Herod undoubtedly saw himself not merely as the patron of grateful pagans but also as the protector of Jewry outside of Palestine, whose Gentile hosts he did all in his power to conciliate.

Unfortunately, there was a dark and cruel streak in Herod's character that showed itself increasingly as he grew older. His mental instability, moreover, was fed by the intrigue and deception that went on within his own family. Despite his affection for Mariamne, he was prone to violent attacks of jealousy; his sister Salome (not to be confused with her great-niece, Herodias' daughter Salome) made good use of his natural suspicions and poisoned his mind against his wife in order to wreck the union. In the end Herod murdered Mariamne, her two sons, her brother, her grandfather, and her mother, a woman of the vilest stamp who had often aided his sister Salome's schemes. Besides Doris and Mariamne, Herod had eight other wives and had children by six of them. He had 14 children.

In his last years Herod suffered from arteriosclerosis. He had to repress

a revolt, became involved in a quarrel with his Nabataean neighbours, and

finally lost the favour of Augustus. He was in great pain and in mental

and physical disorder. He altered his will three times and finally disinherited

and killed his firstborn, Antipater. The slaying, shortly before his death,

of the infants of Bethlehem was wholly consistent with the disarray into

which he had fallen. After an unsuccessful attempt at suicide, Herod died.

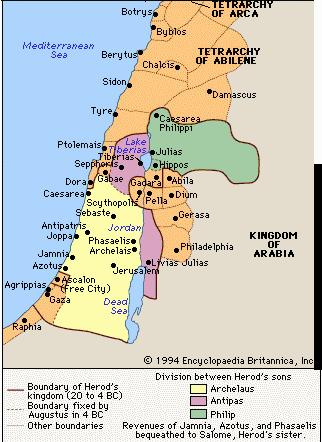

His final testament provided that, subject to Augustus' sanction, his realm

would be divided among his sons: Archelaus should be king of Judaea and

Samaria, with Philip and Antipas sharing the remainder as tetrarchs.

(S.H.P.)

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

The age of the Enlightenment in the second half of the 18th century, with its growth of religious toleration and universal and liberal ideals, laid the foundation in western Europe and North America for the emancipation of the Jews and for their participation as citizens in the life of the nations in the midst of which they lived and whose members they became. The consequence was less emphasis among the Jews on traditional religious attitudes and more on assimilation of Western secular culture. This movement emerged also in Germany, where Moses Mendelssohn (1729-86), a philosopher and a friend of the great German writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, emphasized the spiritual and universal aspects of Judaism. The younger Jewish generation gladly seized the opportunity of intellectual enrichment and civic freedom that the new movement, originally called by the Hebrew name Haskala (Enlightenment), offered. Some went the way of complete assimilation, including the abandonment of the faith of their fathers. Others found their place as citizens of the Jewish faith in the new liberal and egalitarian societies emerging in the 19th century in western Europe and North America. Still others applied the new methods of Western scholarship to a study of the Jewish past and produced, especially in Germany, works of lasting value in the rediscovery and reinterpretation of the ancient heritage. Some wealthy Jews--among them Sir Moses Montefiore and the Rothschild family--tried to help their coreligionists in less fortunate lands, especially in eastern Europe and in the Middle East, by establishing schools and introducing them to agriculture and to various trades. For reasons of religious piety, a small number of Jews, supported by donations from outside, settled in Palestine.

The interest in a return of the Jews to Palestine was kept alive in the first part of the 19th century in part by Christian millenarians, especially in Great Britain. Among Jews pleading then for a Jewish settlement or state was the American Mordecai Manuel Noah (1785-1851), who in 1813 became U.S. consul in Tunis and later high sheriff and surveyor of the port of New York. In 1825 he acquired Grand Island in the Niagara River and invited the Jews of the whole world to create a Jewish state, Ararat, there. In 1844 he pleaded with the Christian world in Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews to help the Jews resettle in Palestine. More important but not more successful were the attempts by Lord Shaftesbury, Sir Laurence Oliphant, and others in Great Britain to create a Jewish state in Palestine. Some political writers thought of a Jewish state in the Holy Land as a means of assuring the overland route to India. Others were inspired by religious or mystic ideas, "anxious to fulfill the prophecies and bring about the end of the world," as was the eccentric Oliphant. He was accompanied on one of his visits to the Middle East by Naphtali Herz Imber (1856-1909), a Hebrew poet of Polish origin, famous in the history of Zionism as the author of "Ha-Tiqva" ("The Hope"), which became the anthem of Zionism and of Israel, and of "Mishmar ha-Yarden" ("The Watch on the Jordan"), a popular nationalist song.

These early sympathies with the return to Zion in the English-speaking

world found their best literary portrayal in George Eliot's novel Daniel

Deronda (1876). A German socialist, Moses Hess (1812-75), influenced by

the example set by the unification of Italy, gave the first theoretical

expression to Zionism among Jews, Rome and Jerusalem (1862; Eng. trans.

1918). This short book, which contained many thoughts later widely accepted

by Jewish nationalists, combined ethical socialism, fervent nationalism,

and religious conservatism. Hess believed that the historical ideal of

the Jewish people could be realized only in their own historic homeland.

He insisted that a moral and spiritual regeneration must precede the settlement

there. He hoped that France, which he venerated as the home of the Revolution,

would protect the Jewish settlement because it would wish to see the bridge

across the Middle East held by a friendly people. Hess's book attracted

no attention when it appeared. Only decades later was it rediscovered by

the Zionist movement, which had by then developed in eastern and central

Europe.

b. May 2, 1860, Budapest, Hungary, Austrian Empire [now in Hungary]

d. July 3, 1904, Edlach, Austria

founder of the political form of Zionism, a movement to establish a

Jewish homeland. His pamphlet The Jewish State (1896) proposed that the

Jewish question was a political question to be settled by a world council

of nations. He organized a world congress of Zionists that met in Basel,

Switz., in August 1897 and became first president of the World Zionist

Organization, established by the congress. Although Herzl died more than

40 years before the establishment of the State of Israel, he was an indefatigable

organizer, propagandist, and diplomat who had much to do with making Zionism

into a political movement of worldwide significance.

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

The British government, which had made secret and conflicting arrangements

with France and Russia for the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire and

the establishment of spheres of influence over former Ottoman lands, and

with Arab leaders for postwar influence, hoped that a declaration in favour

of Zionism would help to rally Jewish opinion, especially in the United

States, to the side of the Allies and that the settlement in Palestine

of a Jewish population attached to Britain by ties of sentiment and interest

might help to protect the approaches to the Suez Canal and the road to

India. The Balfour Declaration fell short of the expectations of the Zionists,

who had asked for the reconstitution of Palestine as "the" Jewish national

home. Instead, the Balfour Declaration envisaged only the establishment

in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. The declaration,

nevertheless, aroused enthusiastic hopes among Zionists and seemed the

fulfillment of Herzl's hopes. It was endorsed by the principal Allied powers,

and, through its acceptance by the Conference of San Remo in 1920, it became

an instrument of British and international policy. The council of the League

of Nations approved on July 24, 1922, a British mandate over Palestine

that included the Balfour Declaration in the preamble and various provisions

dealing with facilitating Jewish immigration. Article 25 of the mandate

gave Britain power to postpone or withhold the provisions of the mandate

with regard to the area east of the Jordan River, and on Sept. 22, 1922,

the British officially announced that the Balfour Declaration would not

apply to that area (amounting to about three-fourths of the whole) and

that the area would be closed to Jewish immigration. The mandate had been

officially interpreted in a statement of June 3, 1922, in which Winston

Churchill, the British colonial secretary, announced that the declaration

meant not the "imposition of a Jewish nationality upon the inhabitants

of Palestine as a whole, but the further development of the existing Jewish

community, with the assistance of Jews of other parts of the world, in

order that it may become a centre in which the Jewish people as a whole

may take, on grounds of religion and race, an interest and a pride." His

Majesty's government, he announced, had not contemplated at any time, as

appeared to be feared by the Arabs, "the disappearance or the subordination

of the Arabic population, language, or culture in Palestine."

(H.K.)

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

The limits on immigration set in the 1939 White Paper were soon rendered moot. As eastern Europe fell under German domination, and especially when the systematic slaughter of the Jews of Europe began in 1942, many more Jews sought refuge in Palestine by illegal immigration. Despite British efforts to reimpose controls on immigration after World War II (the most notorious instance being the interception in 1947 of the Exodus, a ship carrying about 4,500 European Jews to Palestine), the number of refugees continued to increase.

As the Jewish population grew with this increase in refugees, the nature of Zionist activity in the country began to change, tending more toward violence. A secret Jewish army called Haganah ("Defense") was formed in 1920. Until 1936 Haganah restricted itself to purely defensive action, but during the years of the Arab revolt it became more aggressive; it also received some legal recognition when the British administration formed a Jewish Settlement Police drawn exclusively from Haganah and placed nominally under British command. In 1931 a more clandestine Jewish militia representing the extreme revisionist party within the World Zionist Organization had been formed--the Irgun Zvai Leumi ("National Military Organization"). During the early years of the war, Irgun followed the lead of the Jewish Agency and cooperated with Haganah; it soon resumed its extremist course, however, as Jewish refugees freshly arrived from Poland joined its ranks and took over its control. The Irgun leaders were convinced that Britain had betrayed the Zionist cause--an opinion that was shared by another extremist organization, the Stern Group, or Gang, whose leader, Abraham Stern, was killed in a British police raid in 1942. In the last years of the war, the Irgun and the Stern Group intensified its terror against the British.

Meanwhile, the Jewish Agency, under its veteran leader Chaim Weizmann

and younger leaders such as David Ben-Gurion, tried to maintain British

goodwill by offering help to the British war effort. They proposed formation

of a Jewish Legion that would undertake the defense of Palestine. Though

reluctant to sponsor a Zionist force, the British army eventually formed

a brigade of Jewish volunteers that was active late in the war in Africa

and Europe.

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Herzl molded Zionism into a political movement of worldwide significance. He became its indefatigable organizer, propagandist, and diplomat. He convened in August 1897 the first Zionist Congress at Basel, Switz., which drew up a constitution for the movement. His friend Max Nordau participated in drawing up the Basel program of the movement, which proclaimed that "Zionism strives to create for the Jewish people a home in Palestine secured by public law."

To that end the movement was to promote on suitable lines the colonization of Palestine by Jewish rural and industrial workers; to reorganize the whole of Jewry by means of appropriate local and international institutions, in accordance with the laws of each country; to strengthen and foster Jewish national sentiment; and to obtain government consent where necessary to the attainment of the Zionist aims.

The centre of the movement was established in Vienna, where Herzl published the official weekly Die Welt ("The World"). The congresses met every year until 1901 and then every two years. Meanwhile Herzl entered into negotiations with the Ottoman government in order to receive a charter establishing Palestine's autonomy, but the sultan rejected the proposals. Only in England did Herzl find sympathy, and for that reason he established the financial instruments of the movement in London. In 1903 the British government offered an area of 6,000 square miles (15,540 square kilometres) to the Zionist organization in the uninhabited highlands of Uganda. This offer led to violent controversy and even a split in Zionist ranks. A minority under the leadership of Israel Zangwill was willing to accept the offer. Members of this minority founded in 1905 the Jewish Territorial Organization with the aim of finding an autonomous territory for those Jews who could not or did not wish to remain in the countries in which they lived. The majority of the Zionists, most of them from Russia, insisted on Palestine as the only field of activity for Zionism, and the seventh Zionist Congress in 1905 rejected any colonization outside Palestine and its neighbouring countries. In 1904, in the midst of this bitter debate, Herzl, only 44 years old, died.

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britanni

After Suez, 'Arafat went to Kuwait, where he worked as an engineer and set up his own contracting firm. While there, he was a cofounder of Fatah, which was to become the leading military component of the PLO. After being named chairman of the PLO in 1969, he became commander in chief of the Palestinian Revolutionary Forces in 1971 and, two years later, head of the PLO's political department. Subsequently, he directed his efforts increasingly toward political persuasion rather than confrontation and terrorism against Israel. In November 1974 'Arafat became the first representative of a nongovernmental organization--the PLO--to address a plenary session of the UN General Assembly.

In 1982 'Arafat became the target of criticism from various Syrian-supported factions within the PLO and from the Syrians. The criticisms escalated after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon forced 'Arafat to abandon his Beirut headquarters at the end of August 1982 and set up a new base in Tunisia; he shifted to Baghdad, Iraq, in 1987. 'Arafat was subsequently able to reaffirm his leadership as the split in the PLO's ranks healed.

On April 2, 1989, 'Arafat was elected by the Central Council of the

Palestine National Council (the governing body of the PLO) to be the president

of a hypothetical Palestinian state. In 1993 'Arafat, as head of the PLO,

formally recognized Israel's right to exist and helped negotiate the Israel-PLO

accord, which envisaged the gradual implementation of Palestinian self-rule

in the West Bank and Gaza Strip over a five-year period. 'Arafat began

directing Palestinian self-rule in 1994, and in 1996 he was elected president

of the Palestinian Authority, which governed Palestinian-controlled areas

of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Rabin graduated from Kadourie Agricultural School in Kfar Tabor and in 1941 joined the Palmach, the Jewish Defense Forces' commando unit. He participated in actions against the Vichy French in Syria and Lebanon. During the Israeli war of independence (1948), he directed the defense of Jerusalem and also fought the Egyptians in the Negev. He graduated (1953) from the British staff college, became chief of staff in January 1964, and conceived the strategies of swift mobilization of reserves and destruction of enemy aircraft on the ground that proved decisive in Israel's victory in the Six-Day War.

In 1968, on retirement from the army, Rabin became his country's ambassador to the United States, where he forged a close relationship with U.S. leaders and procured advanced American weapons systems for Israel. He drew fire from Israeli hard-liners because he advocated withdrawal from Arab territories occupied in the 1967 war as part of a general Middle East peace settlement.

Returning to Israel in March 1973, Rabin became active in Israeli politics. He was elected to the Knesset (parliament) as a member of the Labour Party in December, joining Prime Minister Golda Meir's cabinet as minister of labour in March 1974. After Meir resigned in April 1974, Rabin assumed leadership of the party and became Israel's fifth (and first native-born) prime minister in June. As Israel's leader he acted as both dove and hawk--securing a cease-fire with Syria in the Golan Heights but ordering a bold raid at Entebbe, Uganda, in July 1976, in which Israeli and other hostages were rescued after their plane was hijacked by Palestinian terrorists.

Rabin was forced to call a general election for May 1977, but in April, during the electoral campaign, he relinquished the prime ministership and stepped down as leader of the Labour Party after it was revealed that he and his wife had maintained bank accounts in the United States, in violation of Israeli law. He was replaced as party leader by Shimon Peres.

Rabin served as defense minister in the Labour-Likud coalition governments from 1984 to 1990, responding forcefully to an uprising by Palestinians in the occupied territories. In February 1992, in a nationwide vote by Labour Party members, he regained leadership of the party from Peres. After the victory of his party in the general elections of June 1992, he again became prime minister.

As prime minister, Rabin put a freeze on new Israeli settlements in the occupied territories. His government undertook secret negotiations with the PLO that culminated in the Israel-PLO accords (September 1993), in which Israel recognized the PLO and agreed to gradually implement limited self-rule for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. In October 1994 Rabin and King Hussein of Jordan, after a series of secret meetings, signed a full peace treaty between their two countries.

The territorial concessions aroused intense opposition among many Israelis,

particularly settlers in the West Bank. While attending a peace rally in

November 1995, Rabin was assassinated by a Jewish extremist.

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

b. Aug. 16, 1923, Wolozyn, Poland [now Valozhyn, Belarus]

original name SHIMON PERSKI Israeli statesman, leader of the Israel

Labour Party (1977-92 and 1995-97) who served as prime minister of Israel

in 1984-86 and 1995-96. In 1993, in his role as foreign minister, Peres

helped negotiate a peace accord with Yasir 'Arafat, chairman of the Palestine

Liberation Organization (PLO), for which they, along with Israeli Prime

Minister Yitzhak Rabin, were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace

in 1994.

Peres immigrated with his family to Palestine in 1934. In 1947 he joined

the Haganah movement, a Zionist military organization, under the direction

of David Ben-Gurion, who soon became his political mentor. When Israel

achieved independence in May 1948, Prime Minister Ben-Gurion appointed

Peres, then only 24, head of Israel's navy. In 1952 he was appointed deputy

director general of the Defense Ministry, later serving as general director

(1953-59) and deputy defense minister (1959-65), during which service he

stepped up state weapons production, initiated a nuclear-research program,

and established overseas military alliances, most notably with France.

Peres resigned in 1965 to join Ben-Gurion in founding a new party, Rafi,

in opposition to the succeeding prime minister, Levi Eshkol.

The Rafi Party was unsuccessful, and in 1967 Peres initiated merger negotiations between the Mapai (Ben-Gurion's former party) and the Ahdut Avodah, a more leftist workers' party, that led to the establishment of the Israel Labour Party, of which he became deputy secretary-general. He became defense minister in the Labour Cabinet of Rabin in 1974.

In 1977 Peres became head of the Labour Party and, as such, was twice defeated by Menachem Begin as a candidate for prime minister (1977, 1981) before winning access to the post after the indecisive elections of 1984. In September 1984 Peres and Yitzhak Shamir, head of the Likud party, formed a power-sharing agreement, with Peres as prime minister for the first half of a 50-month term and Shamir as deputy prime minister and foreign minister; the roles were reversed for the second 25-month period. Under Peres's moderate and conciliatory leadership, Israel withdrew its forces in 1985 from their controversial incursion into Lebanon. After similarly indecisive elections in 1988, the Labour and Likud parties formed another coalition government with Peres as finance minister and Shamir as prime minister; this coalition lasted only until 1990, when Likud was able to form a government without Labour support.

In February 1992, in the first primary election ever to be held by a

major Israeli party, Peres lost the Labour leadership to Rabin. When Labour

won in the general elections in June and Rabin became prime minister of

Israel in July, Peres was brought into the Cabinet as foreign minister.

After the Israel-PLO accord was signed in 1993, Peres handled the negotiations

with the PLO over the details of the pact's implementation. Following the

assassination of Rabin in 1995, Peres took over as prime minister. In May

1996 he was narrowly defeated in his bid for reelection by Benjamin Netanyahu

of the Likud party. Peres declined to seek reelection as leader of the

Labour Party in 1997. His memoir Battling for Peace was published in 1995.

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Begin joined the militant Irgun Zvai Leumi and was its commander from 1943 to 1948. After Israel's independence in 1948 the Irgun formed the Herut ("Freedom") Party with Begin as its head and leader of the opposition in the Knesset (Parliament) until 1967. Begin joined the National Unity government (1967-70) as a minister without portfolio and in 1970 became joint chairman of the Likud ("Unity") coalition.

On May 17, 1977, the Likud Party won a national electoral victory and on June 21 Begin formed a government. He was perhaps best known for his uncompromising stand on the question of retaining the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, which had been occupied by Israel during the Arab-Israeli War of 1967. Prodded by U.S. President Jimmy Carter, however, Begin negotiated with President Anwar el-Sadat of Egypt for peace in the Middle East, and the agreements they reached, known as the Camp David Accords (Sept. 17, 1978), led directly to a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt that was signed on March 26, 1979. Under the terms of the treaty, Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula, which it had occupied since the 1967 war, to Egypt in exchange for full diplomatic recognition. Begin and Sadat were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1978.

Begin formed another coalition government after the general election

of 1980. Despite his willingness to return the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt

under the terms of the peace agreement, he remained resolutely opposed

to the establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

In June 1982 his government mounted an invasion of Lebanon in an effort

to oust the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) from its bases there.

The PLO was driven from Lebanon, but the deaths of numerous Palestinian

civilians there turned world opinion against Israel. Israel's continuing

involvement in Lebanon, and the death of Begin's wife in November 1982,

were probably among the factors that prompted him to resign from office

in October 1983.

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Egypt and Israel had technically been at war since Israel's founding in 1948, and the latter had occupied the Sinai Peninsula since taking that territory from Egypt in the course of the Six-Day War of 1967. The Camp David Accords had their origin in Sadat's unprecedented visit to Jerusalem on November 19-21, 1977, to address the Israeli government and Knesset (parliament); this was the first visit ever by the chief of state of an Arab nation to Israel.

Sadat's visit initiated peace negotiations between Israel and Egypt later that year that continued sporadically into 1978. With a deadlock having been reached, both Sadat and Begin accepted President Carter's invitation to a U.S.-Israeli-Egyptian summit meeting at Camp David, Md., on Sept. 5, 1978. After 12 days of negotiations mediated by Carter, Sadat and Begin concluded two agreements: one a framework for the conclusion of a peace treaty between Egypt and Israel, and the other a broader framework for achieving peace in the Middle East. The former provided for a phased withdrawal of Israeli forces from the Sinai and that region's full return to Egypt within three years of the signing of a peace treaty between the two nations. This framework also guaranteed the right of passage for Israeli ships through the Suez Canal. The second, more general framework called in somewhat vague terms for Israel to gradually grant self-government to the Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip and to partially withdraw its forces from those areas in preparation for negotiations on their final status after a period of three years.

The peace treaty that Israel and Egypt signed on March 26, 1979, closely

reflected the Camp David Accords. The treaty formally ended the state of

war that had existed between the two countries, and Israel agreed to withdraw

from the Sinai Peninsula in stages. The treaty also provided for the establishment

of normal diplomatic relations between the two countries. These provisions

were duly carried out, but Israel failed to implement the provisions calling

for Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza areas.

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

It was in foreign affairs that Sadat made his most dramatic efforts. Feeling that the Soviet Union gave him inadequate support in Egypt's continuing confrontation with Israel, he expelled thousands of Soviet technicians and advisers from the country in 1972. The following year he launched, with Syria, a joint invasion of Israel that began the Arab-Israeli war of October 1973. The Egyptian army achieved a tactical surprise in its attack on the Israeli-held Sinai Peninsula, and, though Israel successfully counterattacked, Sadat came out of the war with greatly enhanced prestige as the first Arab leader to actually retake some territory from Israel.

After the war, Sadat began to work toward peace in the Middle East. He made a historic visit to Israel (November 19-20, 1977), during which he traveled to Jerusalem to place his plan for a peace settlement before the Knesset (Israeli Parliament). This initiated a series of diplomatic efforts that Sadat continued despite strong opposition from most of the Arab world and the Soviet Union. The U.S. president Jimmy Carter mediated the negotiations between Sadat and Begin that resulted in the Camp David Accords (September 17, 1978), a preliminary peace agreement between Egypt and Israel. Sadat and Begin were awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1978; and their continued political negotiations resulted in the signing on March 26, 1979, of a treaty of peace between Egypt and Israel, the first between the latter and any Arab nation.

While Sadat's popularity rose in the West, it fell dramatically in Egypt because of internal opposition to the treaty, a worsening economic crisis, and Sadat's suppression of the resulting public dissent. He was assassinated by Muslim extremists while reviewing a military parade commemorating the Arab-Israeli war of October 1973.

Sadat's autobiography, In Search of Identity, was published in 1978.

Copyright © 1994-2000 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.